Just about a year ago, Mieshia Smith, a counselor with Child Crisis Arizona, began working with a 4-year-old girl who was having trouble forming attachments to her paternal grandmother who had formally adopted her. The girl was throwing fits when angry, yelling at her new adoptive mother and crying. Mieshia began working with both the child individually and the family weekly. Over time they learned that the girl responded better when there was less rushing from one appointment to the next. They learned how to talk about, express and manage emotions, taking the Anger Management and Relatives as Parents classes. Nine months later, the family is finishing up the last of their counseling sessions as the girl continues to communicate more clearly about her emotions and manage them appropriately.

According to Mieshia, many of the children who have suffered from abuse or neglect are behind in their emotional development and have difficulty expressing and regulating their emotions.

Emotion regulation is involved in how we feel emotions, how we pay attention to them, how we think about these feelings and how we behave – from our physiological reactions (e.g., increased heart rate) to our purposeful coping behaviors. Emotion regulation develops primarily through the parent-child relationship. Children need help making sense of how they feel, understanding why they are feeling the way they do, and figuring out what they can do about it.

Children who have experienced difficult and traumatizing circumstances have many feelings but may not know exactly what they are or how to express them.

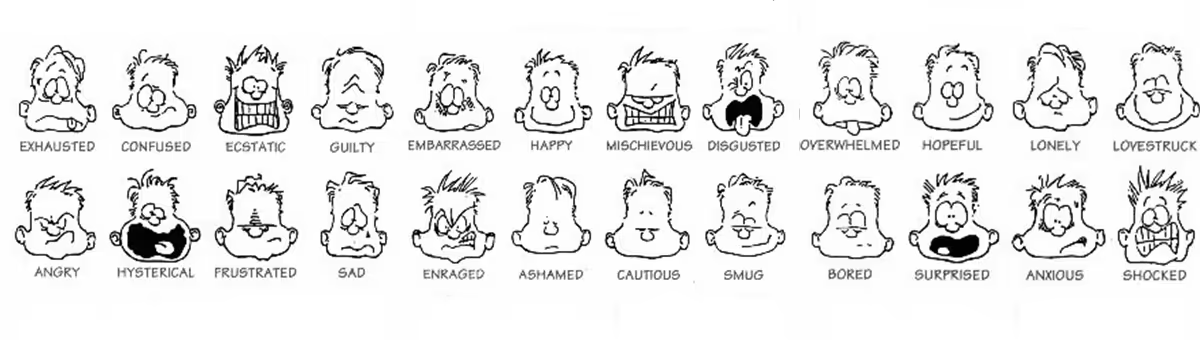

“I found that abused and neglected children often come to counseling knowing only three emotions: happy, sad and angry,” says Mieshia. “There are many other emotions they may be experiencing. Helping them identify the emotion and speak about it normalizes the emotion. Then the conversation can turn to how to address it.”

Through speaking and listening, Mieshia helps a child identify new emotions, like disappointment, frustration, resentment, excitement, jealousy, anxiety and others. She uses a technique called reflective listening. This involves carefully listening to what the child says and then mirroring back to them the feeling they are experiencing. It might sound like, “I see you are (feeling word) because (describe the situation). Would you agree?”

When children are younger and have difficulty discussing their emotions, Mieshia teaches the reflective listening skill to the parents. She provides them with a long list of “feeling” words to use when listening to and speaking with their children.

The key is really listening to what the child expresses and helping them define and find the words for their emotions, rather than explain them away.

“New foster or adoptive parents might be tempted to tell a child ‘That won’t happen again’ or ‘There’s no reason for you to feel that way anymore.’” she says. “Don’t dismiss their feelings. Listen to them. Let them know all their feelings are okay. They need to know what they are in order to react appropriately.”

She says many foster or adoptive parents often expect the children that come into their home to have a period of adjustment that is shorter than what’s realistic. Just how long it can take can be a surprise.

“When things aren’t moving as quickly as they anticipate, nearly all foster parents think, in general, ‘My kid has a problem. I’m doing something wrong.’ I want to tell them emotional development is a slow process. There’s no magic pill or instruction book to move it along. You just have to try things, talk through it, take what works and build on that. Discard what didn’t. Tweak it and try again.”

Success should be measured by small increments.

“Parents have to find the positive in a situation and focus on that. If a tantrum that formerly lasted 30 minutes now lasts 25, that’s a success. Good job! Keep it up!” Mieshia says. “Parents aren’t told enough that they are doing a good job. They are. They’re doing a fabulous job. They need to hear that. As often as they cheer on the kids, they need to cheer themselves.”